NEIL LEADBEATER Reviews

Letters To A Young Brown Girl by Barbara Jane Reyes

(BOA Editions Ltd., Rochester, NY, 2020)

Letters To A Young Brown Girl is the sixth and latest book of poetry by Filipina-American poet, writer, activist and cultural worker, Barbara Jane Reyes. Her previous poetry collections include Gravities of Center, Poeta en San Francisco, Diwata, To Love As Aswang and Invocation to Daughters.

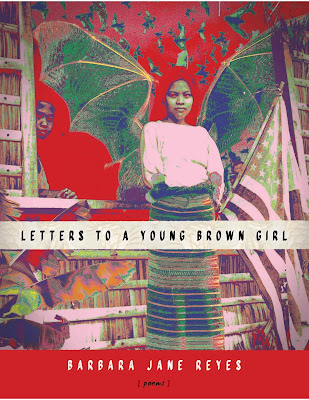

The first thing to note about this book is its striking cover. In the centre, there is an image of young, brown woman dressed in a tribal skirt and white blouse with outspread wings behind her back. These wings could be bat wings, banana leaves or the wings of an angel. There are birds flying overhead. In the background there is a wooden hut indigenous to the Philippines. From the hut the face of someone looks out on the world while to the right of the picture there is an American flag.

Letters To A Young Brown Girl is a work in three movements. At its core, this is a book about perception: how we perceive the world, how the world perceives us and how we perceive ourselves. It reads like a musical composition, not only is it very aural in its soundscape – a sort of Vivace, Andante, Allegro, but it is also complex in its different layers of text and it sits within a tight, well-ordered structure. Frequent use of repetition as a literary device parallels the idea of recurring themes in musical composition. It grounds the reader in the heart of the argument and knits the collection into a cohesive whole.

The first movement, ‘Brown Girl Designation,’ could well be described as a stream of invective – a series of outbursts emerging in the form of prose poems that contain within them a great deal of emotional force. Writing at a time of political unrest and upheaval, there is so much anger here, it is cathartic even to read it. This is not to say that Reyes has just written down the first thing that has come into her head – far from it – the whole section has been extremely well thought out. Note the title – that italicised ‘n’ in ‘Designation’. It is there for a purpose. It makes us stop and look at the word in a new way. It could contain within it two words: 'design’ and ‘nation’. Both words are loaded with meaning.

The section opens with a series of definitions rather in the manner of an insurance claim defining specific terms, and then there are questions that the young brown girl might like to consider. These questions are phrased in such a way as to make the reader proceed with caution. They are as subtle and beguiling as the serpent in Eden. Here is a taste of them:

what’s it like to be so treasured to be trafficked,

what’s it like to be locked in for your own good so no one will get their oily fingerprints on you, so that no one can hear your soft, soft asking voice,

what’s it like when they mispronounce your alien name and shrug, when they tell you your ass should be deported…

The section closes with a ‘Brown Girl Glossary of Terms’ exploring terminology such as internal colonialism, decolonization, white privilege, Pinoy, Pinay and Pakikipagkapwa-tao followed by a ‘Brown Girl Manifesto’ whose repetitious phrase ‘Because so much depends upon…’ has that William Carlos Williams American ring to it.

The middle movement, ‘Brown Girl Mixtape,’ comprises 20 short poems whose titles are taken from song tracks dating from 1964 to 2017. So often, music, especially popular music, defines the moment in which it was written: it is a product of its own time.

Opening with a couple of sentences that read like something out of an instruction manual on relaxation techniques, Reyes begins to ease that knot of tension that was felt in the first part of the book:

Squeeze your hand into a fist. Now, loosen just a bit.

The final lines invite us to take note of our altered pulse rate, to see how it has begun to slow down as a result of this change of gear:

…Press your index finger and tall finger

into the underside of your jawbone, and count.

In ‘Track: “Firewoman,” Barbie Almabis (2005)’ I particularly liked the way in which Reyes used phrases such as ‘grooved edge,’ and ‘cut wax track’ that fitted so well with the image of vinyl. The word ‘break’ and ‘wrecked’ also plays on the fragility of shellac which preceded vinyl. None of these observations have much to do with the prose poem per se but it is interesting to note how these words have slipped into the text at an almost subconscious level.

In this middle movement, where prose poems give way to poems, we see Reyes at her most lyrical. In ‘Track: “Dahil Sa Iyo,” Pinay (1998) she writes:

Do you know how old you were when you first saw the ocean,

How old you were when the ocean first touched you,

How old you were when you knew you were the ocean.

Do you remember its cradle and nudge, its pull and boom, your skin shocked by your

own pinpricks and ice, do you remember sinking,

How were you ever so new, swaying into something so immense, so beyond sight.

….

Do you remember the rocks. How old were you when you returned.

The final movement takes the form of 10 letters and carries the title of the collection: ‘Letters To A Young Brown Girl’. The deliberate use of the indefinite article denotes that these letters are being addressed to all young brown girls, not to a specific one. They speak of the universality of this poet’s approach to writing. Since each letter is untitled –you would not normally give a letter a title – for ease of reference, the beginning of the first line is given in square brackets on the contents page.

The first letter focuses attention on the spoken word and the second one on the written word with excursions into penmanship: ‘I want to tell you about my rounded, looping penmanship in berry scented ink’. The next letter is on the topic of keeping diaries and secrets and the fourth one is about silence – listening to it and tuning in to your own heartbeat: ‘What do you find when you sit with yourself inside your silence’. The absence of the question mark at the end of this sentence and at the end of all of the questions in the entire book is deliberate. There are no question marks anywhere. Reyes does not want to turn this into an interrogation. Interrogations carry their own threats. These, after all, are rhetorical questions, ones that are asked in order to create a dramatic effect or to make a point rather than to obtain an answer. Nobody pretends to have answers. The next letter describes another kind of silence. The overwhelming, unsettling silence that is inflicted by subjection:

They proposition you and grab your ass. They are impressed you do not protest. They love your nodding and smiling at exactly the right moments.

The last letter in this series returns to the subject of the spoken word bringing the cycle full circle.

The final epistolary poem is cast in the form of one hundred FAQs (frequently asked questions) from writers. Instead of the formal Q&A we are accustomed to see, Reyes only provides the answers (in other words, the questions are not stated, they are simply implied by the answers).

Letters To A Young Brown Girl covers a great deal of ground: it touches upon race, ethnicity, religion, gender and nationality. To the girl who is taught to be small, to know her place, who is concerned that no one will ever hear her, Reyes gives her the affirmation that she is listening and her book is uplifting in the sense that she leads us time and again to our inner selves (the loób) where we can pause, take stock, and see the beauty that lies inside.

*****

Neil Leadbeater is an author, essayist, poet and critic living in Edinburgh, Scotland. His work has been published widely in anthologies and journals both at home and abroad. His publications include Librettos for the Black Madonna (White Adder Press, 2011); The Worcester Fragments (Original Plus, 2013); The Loveliest Vein of Our Lives (Poetry Space, 2014); The Fragility of Moths (editura pim, Iași, Romania, 2014); Sleeve Notes (editura pim, Iași, Romania,, 2016); Penn Fields (Littoral Press, 2019) and Reading Between the Lines (Littoral Press, 2020). His work has been translated into French, Dutch, Nepali, Romanian, Spanish and Swedish.

No comments:

Post a Comment