RACHIELLE RAGASA SHEFFLER Engages

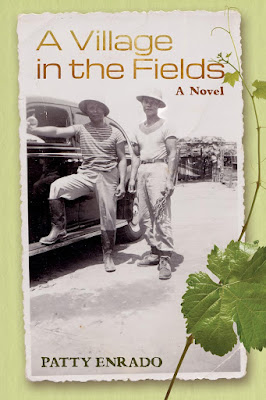

A Village in the Fields by Patty Enrado

(Eastwind Books, Berkeley, 2015)

BOOK LINK

Return to Terra Bella: A Village in the Fields

Mama asked, "Are you coming to Terra Bella?"

Terra Bella means "Beautiful Land," but I had failed to see its beauty when I went there thirty-four years ago. Every Labor Day weekend, Mama and her townmates from all over the world gather in California’s Central Valley to recreate the San Esteban fiesta of their youth. Back home in Ilocos Sur, Philippines, St. Stephen’s Day was bigger than Christmas. The carnival, or perya, came to town, and the sounds of squealing children mingled with rondalla music, plays, folk dances, and a pageant. Colorful streamers stretched from the plaza to the churchyard.

When I first visited Terra Bella, I was a new immigrant, having arrived only three months prior. My cousin, brother, and I sat in the back of my uncle’s van and played a silly game. Whoever first heard the sound of a classic VW Beetle called out, "Slug Bug!" and punched the other two.

A blanket of heat greeted us when we arrived. Dust swirled, and I felt my lungs choke with its fine powder. My skin prickled, and a heat rash came on. My skin took the appearance of a freshly plucked chicken. My head throbbed with a pulsating pain.

“Just like San Esteban,” I thought aloud. I recalled that the locals used to call my sisters and me “Rosy Cheeks.”

I spent all my childhood summers in Ilocos with my grandmother, Lola Andang. She used to shake Johnson’s baby powder all over my body to relieve the itch from the heat rash. It took me about two weeks to acclimate to the warmer weather. When I did, I sat under the acacia trees across the Presidencia to cool off, or went to the beach at Pantalan or Apatot. After three months in the lowlands, I was happy to go back to Baguio, amidst the pine trees and the crisp mountain air. The school year ran from June to March, and the cycle resumed. City girl, country girl.

The San Esteban Circle hosted the fiesta, and the program included singing, dancing, speeches, awards, and socialization. My cousins staged a fashion show, and I played a piano piece. The event's highlight was the crowning of Miss San Esteban, awarded to the highest fundraiser.

In 1988, Mama immigrated and founded the San Esteban Schools Alumni Association. At first, it was met with suspicion, "You are encroaching on our territory,” she heard.

Never one to back down from a fight, Mama persisted, "I am a native daughter of San Esteban." Eventually, the two organizations worked together to sponsor projects or scholarships. Students who received grants wrote back, thanking them for their assistance in their education.

Apart from the fiesta, my only memory of Terra Bella was the smell of water. At someone's house, someone offered me a glass to drink. It had a vague scent of rotten eggs, like the sulfuric aroma of the hot springs down the village where I grew up. After that first visit, I did not have a great desire to go back to the hundred-degree heat, in the dead of summer. Mama asked year after year, and I kept saying no.

In 2020, I resumed a long-forgotten project, updating our family tree. The Covid pandemic forced me to reflect on the brevity of life. I interviewed relatives in earnest and was surprised at how little I knew of our family’s immigration stories. I learned of the Manongs, farmworkers in California, the Sakadas in Hawai’i, and the Alaskeros who endured dismal conditions in the salmon canneries. I began to pay attention. I began to write again, a childhood dream of mine.

I recalled a picture of the fiesta that Mama posted on Facebook a few years back.

"Mama, who was that author signing books at the Terra Bella Fiesta?"

"Gurka, I'll ask."

I laugh when Mama shortens agurayka. "Ok, I will wait."

A few weeks later, she forwarded an email, "That's Lelang Conching's daughter, Patty Enrado. The book is called A Village in the Fields.”

The main character, Fausto Empleo, intrigued me from page one. In his old age, he lived in the Agbayani Village, which was built for the farm workers, called the Manongs. They had nowhere to go after they retired, for they had lost their family connections, or were kicked out of the camps after the 1965 Delano Grape Strike.

Fausto's fascination with America started as a young boy in San Esteban. He learned of this promised land from his teacher Miss Arnold, one of the many educators who sailed to the Philippines aboard the USS Thomas. When he arrived, he sought his cousins in Stockton and Los Angeles. Together, they navigated experiences far from their expectations. In America, they were called brown monkeys, they were spat on, beaten, and kicked out. Everywhere, signs made it clear, “Positively no Filipinos allowed,” or “Dogs and Filipinos not allowed.”

Laws prevented Filipinos from acquiring citizenship, voting, holding office, or marrying white women. Their backs stooped from harvesting asparagus, lettuce, or grapes. What little money they earned, they sent home, sparing a few dollars for entertainment. Some assuaged their homesickness with gambling, and others found solace in the arms of women, either in the brothels or in the taxi dance halls, where a dance cost a dime.

During World War II, Fausto Empleo and his cousins served in a segregated unit with the US Army. The First Filipino Infantry Regiment fought in New Guinea and in the Philippines. After the war, Fausto and his cousin Benny Edralin returned to the US and settled in Terra Bella, where they bought a home and planted vegetables in their garden. It was a step up from the crowded accommodations at the camp.

The Filipino community in Terra Bella grew. Though largely a bachelor society, a few married and started families. They formed the San Esteban Circle and summoned relatives far and wide for the annual fiesta. In one gathering, the attendees included the Abads, Aysons, Edralins, Ealas, Empleos, Orpillas, and Vergaras.

I recognized these names from my family tree, and I looked at Fausto with renewed interest.

In 1965, the Manongs joined the strike, with Larry Itliong at the helm. He proposed to Cesar Chavez for the Filipinos and Mexican workers to band together, instead of breaking each other’s strikes. They formed the United Farm Workers, and after many years, they gained contracts and better working conditions.

I began to follow Patty Enrado's work. In a podcast, she and the host reminisced about growing up in Terra Bella. Patty described the book’s journey, taking seventeen years before it saw print. Her persistence paid off, and it was published in 2015, in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike. In one lecture, Patty described the evolution of Filipino American literature in the United States. From that, I discovered more authors of Filipino descent.

I made up my mind and called Mama. She had just turned eighty last year, and she was excited for the fiesta’s resumption after three years of Covid. Two things made Mama happy—anything San Esteban, and her children around her.

Mama, my sister, my brother, and their families filled one vehicle, and I went with a cousin. I did not hear any VW Beetles chugging on the road. The freeway was full of Teslas, including the one I rode in. My nephew sat with me in the back, but he was preoccupied with his phone. Slug Bug was a figment of the past.

The scenery changed after we passed Grapevine. On the way to Terra Bella, we guessed that the trees laden with brown clusters were pistachios. A few signs for Halos helped us identify the citrus plants as California mandarin oranges. Rows upon rows of grapevines alternated with fields of corn, or vast stretches of emptiness dotted with horses or cows. At Bakersfield, oil derricks pumped for oil. The scene was surreal—an army of mechanical dinosaurs grazing on a desolate landscape.

We arrived at our destination on Avenue 95. We stepped out, and I was glad that the temperature rose no more than eighty-eight degrees. In Terra Bella, as Patty wrote, “It was so hot that your earwax melted.”

The brick structure was exactly as I remembered it, and as Patty described, “The Veterans Memorial Building was erected after World War II, with a main hall that boasted floor-to-ceiling windows and an elevated stage, a commercial size kitchen, and a banquet room whose walls were lined with photographs of American servicemen. Gamblers set up tables and chairs in the corner of the hall to play rummy and mahjong.”

I felt like stepping into a book and real life at the same time.

I had asked Patty if she was going to the fiesta, but she had other plans. On her Facebook page, memories of the fiesta popped up, and if no one paid attention to the dates, it seemed that she and I were at the same event, for the pictures were taken in the same hall, and with the same people. San Estebanians have a distinct look. Like my mother and grandmother, many have fair skin, oval faces, prominent cheekbones and high foreheads. They sound the same, speaking Ilocano with a singsong ayog, or accent.

People greeted us, “La, mangankayon,” and led us to the kitchen.

We loaded our plates with dinengdeng, higado, rice, shrimp, and roasted eggplants with fresh cherry tomatoes in bagoong. For dessert, we ate bibingka and biko. I popped freshly picked grapes into my mouth and understood the name, Terra Bella. Only a beautiful earth can produce such sweetness. I was grateful for cold bottled water.

A lady approached me and introduced herself as Manang Nining, and drew a map on a napkin. "This is your Lola’s house, across from Nana Cion's, then the Quebrals. Our house is in the cul-de-sac."

She cemented our bonds, “The eastern part of town, diyay daya, is owned by the Abad, Ayson, and Benitez families.” My Lola was a Benitez before she married my grandfather, Abdon Eleccion Vergara.

Mama loves to trace relations and knew if someone was our third or fifth cousin, and from what branch. Sometimes, we were related on both sides of her tree. I inherited the love of genealogy from her. Ever the Girl Scout, she had “a place for everything and everything in its place.”

Mama introduced me to the Catálogo Alfabético de Apellidos, a decree issued in 1849 by Governor General Narciso Claveria. This was done to facilitate taxation for the Spanish colonial government. Also known as the alphabetization decree, it assigned surnames published in the catalog. In the presence of the parish priest and the barangay head, the father from each household chose the family’s last name. Previously, natives named themselves after an attribute, a physical description, an animal, a plant, or a geographical landmark. Only those who proved that they had used a family name for at least four generations were allowed to retain it.

San Esteban was assigned the letter E. Thus, Ea, Eala, Edralin, Empleo, Eleccion, Espejo, Elaydo, Esperanza, and Europa became common last names. In tracing the family tree, Mama showed me how to distinguish San Esteban natives from the dayo, or foreigners such as my father. His hometown in Santa Catalina was assigned the letter R, so my paternal relatives are Ragasas, Refuerzos, Rapacons, Rafanans, Raguntons, and Rabes. My relatives in Tagudin adopted last names starting with the letter L, while my best friend’s family from Narvacan took the letter C.

There were two groups of people at the fiesta – kailians or townmates, and kabagians or relatives. By the end of the evening, Mama traced the lineages and confirmed Manang Nining’s claim, “Basta, agkakabagiantayo amin.” We are all related.

We enjoyed a weekend filled with good food, stories, dances, speeches, and presentations. Pageant candidates danced with their supporters, and they dropped a donation into their fundraising box. My niece made HRH First Princess, happy to do her part for Lola’s hometown. Women paraded a dazzling array of Filipiniana dresses embroidered with intricate designs, while the men sported matching barong tagalogs.

As we wrapped up, I told my siblings about Patty's book and described how Fausto, in his old age, longed for the pristine white sands of Apatot Beach, and the shade of the giant acacias in the plaza. They smiled in recognition. Though we protested those trips to the province, in hindsight, we agreed with Mama, “San Esteban is a slice of paradise.”

Mama’s hearing has diminished over time, but she perked up and joined our conversation.

"Fausto? Fausto Empleo? Your Lolo’s father is Domingo Empleo Vergara. Fausto is surely our relative."

I opened my mouth, then zipped it. I didn't have the heart to correct her. Who’s to say that Fausto was but a figment of Patty Enrado’s imagination? He could be my cousin’s Lolo, Eustacio Abad, who labored in Terra Bella for many years. Manang Emy told me, “Before Papa came to Canada, he never worked a day in his life. He was spoiled, because Lelong sent dollars from America.”

Fausto Empleo could be another name for Uncle Jim Rafanan. He sheltered newly arrived relatives, professionals who immigrated under the auspices of Hart-Celler, the Immigration Act of 1965. Though his home was simple, it was his crowning achievement, because “Back then, we slept under the trees. We were not allowed to own a home.”

I looked at Mama’s satisfied smile at adding yet another leaf to our family tree. I nodded, "Yes, Mama, Fausto Empleo must be a long-lost Uncle."

*****

Rachielle Ragasa Sheffler is working on a memoir on her family’s immigration, and translating her late father’s Ilocano short stories published in Bannawag in the 1960s to 1970s. She is a member of the International Memoir Writers Association and San Diego Writers, Ink. When not writing, she works as a clinical laboratory scientist in San Diego, CA.