Editor’s Note: This issue inaugurates a new Feature: “Lit in 5!” Through this format, two authors ask five questions to each other about each other’s book. In this case, Vince Gotera asks about Tony Robles’ Where the Warehouse Things Are and Tony Robles asks about Vince Gotera’s Dragons & Rayguns.

Authors are invited to partner up with other authors to do the same. At least one of the two authors must be Filipino. I look forward to your conversations. The deadline will be the same general deadline for each issue; for the next issue, deadline is April 15, 2025 though I'm happy to take your features earlier.

—Eileen R. Tabios

LIT IN 5!—TONY ROBLES and VINCE GOTERA

(We begin with Tony Robles; scroll down for Vince Gotera)

Vince Asks Tony Robles:

1.

Tony, I have really relished reading Where the Warehouse Things Are (Redhawk Publications, 2024). Thank you very much. You are well-known as “The People’s Poet” ... how do this book and its poems fit in with that self-image and reputation for you?

The funny thing about “The People’s Poet” is that I got that moniker from Muhammad Ali. He was known as the People’s Champion. He was my hero growing up. He was like a god in my household. His fights were big events, huge ones. He represented the physical and mental strength, of confidence and belief in oneself. I have struggled most of my life from a lack of confidence so I guess you can say that I admired that about fighters, the fact that they put it all on the line. The trainer Teddy Atlas said that you don’t really know someone until they’ve been tested, have encountered some kind of resistance. My critical thesis at Vermont College was called Crafting the Punchline: The Parallels Between Boxing and Writing. In the MFA program my focus was on fiction. I learned about desire vs. resistance in a short story or novel. But that impacted me on a deeper level. I saw the elements as parallel to my own struggles as a person, so those craft elements became literal to me in the true sense of my everyday living. One other thing about “The People’s Poet” is that I was reluctant at first to use it. I thought it was perhaps presumptuous or self-aggrandizing. But then I thought, I do write about people. If I wrote about dogs, I’d be the Canine Poet, or cats, the Feline Poet. So, I figured I’d use it.

2.

One of your uncles is the renowned Filipino American poet Al Robles. How do your poems converse with his work? As well as with his personality and his influence on you?

People say to me, your uncle must have sat you down and taught you how to write. He never sat me down and went over my work with a red pen or anything like that. He had tremendous restraint in that way. He knew that I would have to find my way, my path, and he had enough grace to let me walk those baby steps. He gave me books that helped me along the way. He always knew what it was that I needed. He gave me a book by Charles Bukowski called Septuagenarian Stew. That book had a real profound impact on me. It liberated me in that it validated how I was feeling, the isolation and other things. My mother is an editor and book coach. I get any natural ability from her. From my father I get a sense of the absurd and the pain and the reality that the world will be indifferent to you and your efforts. Through my uncle Al I get a sense of grace. That was his gift to me. Grace and perhaps stoicism. I am all over the board at times, with trouble focusing. So I go to the stoic Seneca who said: “Life without design is erratic.” This has helped me become more focused. But from my Uncle Al I picked up on a sense of grace, gentleness. I think that is the most important thing I have going for me.

3.

What are your artistic methods and techniques as a poet? I especially like your surreal touches and sensory details, the play of light and the dance of music, like jazz. How conscious are you about sound? I noticed, for example, the play of “d” sounds in the lines “a dermis of / disarray and deficits / of derelict DNA.” What other craft elements are at play in your poetics?

My late Uncle Anthony was a street minister towards the end of his life. He grew up in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, in the heart of it. He grew up with jazz and all the music and sounds of the Black community. The thing about growing up as immigrants in the Black community was that they never had any misconceptions of what they were. They saw themselves as Black, or Black Filipinos. They didn’t see themselves as white; they didn’t aspire to it. All of my father’s friends were Black. I don’t think he had any Filipino friends until he moved to Hawaii in the early ’80s and got involved in the Filipino martial arts community. But the sounds and rhythms of the music he listened to and the way he spoke, those are what inform me as a poet. A sense of identity, yes, for sure. When I’d visit my uncle Anthony, it was like a ritual. As soon as I set foot in his room he had a record cued up—Afro Filipino by Joe Bataan. He would serenade me. It embarrassed the hell out of me but he never let me forget what I was. And of course the music I grew up with: Tower of Power, the Tempts, The Spinners, War, all of that provides a music bed that I lie and meditate on. I wrote a sonnet in Where the Warehouse Things Are. It’s really the first sonnet I’ve ever written. My approach is to let the poem be what it is going to be. I try not to get in the way. I find that it works best for me this way. Those thoughts and inspirations just come to me, kind of like my cat Francesca. She just showed up one day at the warehouse. She kept coming and after a month or so, I bought a raccoon trap from Ace Hardware and caught her. She has been kind of an editor for my work. Anyway, she’s working on a memoir called, “Scratching Beyond the Surface: From the Streets to Poetry.”

4.

How do you see your work, and specifically the poems in this book, against the background of Filipino American literature as well as Filipino art and writing more generally. For example, the poem “Pallets” is labeled “after Oscar Peñaranda” ... in what ways? I also hear and feel the presence and influence of Carlos Bulosan in your work. And of course, your Uncle Al Robles, as I have already mentioned. Do you think consciously about Filipino tradition in your writing, both in poetry and in fiction?

Oscar Peñaranda is an interesting guy. A really funny guy and a real treasure. He is like one of those uncles who pulls quarters out of your ears. He gives me what I need, through his writing. He is like the eternal uncle. If Al Robles is the Whitman of our community, then I would call Oscar our Shakespeare. He kind of saved me at this warehouse job. I was getting down on myself for some mistakes I’d made at the job and one of Oscar’s stories acted as a reset button. I was never mechanically inclined, to be honest. Perhaps that’s why I am a poet. Anyway, the passage from one of Oscar’s stories was about a young guy working in Alaska trying to help an old man get his defunct ship to set sail. I really identified with that young man. In the passage, the young man says, “But I’m not a mechanic,” to which the old man replies: “Yes, you are!” He smiled and thumped the young man’s chest with his fingertips. “You’re a mechanic of the heart,” he beamed. “The most important engine of them all!” That passage really helped me. In fact, I have it taped to the wall near my desk. Oscar and I have this inside joke. I call him “Mr. Johnny Horton” because he writes about Alaska and I think of that song by Horton called “North to Alaska.” I write about a lot of things, mostly observances of people and situations. My Filipino-ness comes out in a curveball, a curveball stained with kare kare, the sauce from adobo and the black ink from a pot of adobong pusit. In fact, I used that ink to write Where the Warehouse Things Are. I wrote a lot of poems about Hurricane Helene that hit where I live in Western North Carolina. To me, poetry is all over the place. It’s just a matter of recognizing it when it decides to reveal itself.

5.

What is the importance of family to you in the book? Not only your father, your mom, your uncles, but also the family of coworkers in the warehouse? So much love and tenderness in the book.

Well, as Otis sang, “Try a Little Tenderness.” Much of the book is about my reconciling my relationship to my father which is kind of like my relationship to the world. My father was my father but he was also my boss. He had a small business called “The Filipino Building Maintenance Company.” I worked with him while in high school. I couldn’t do anything right, I mean, anything. I couldn’t clean the toilets right, I couldn’t vacuum right, nothing. So when I got out in the world, I was kind of spooked. I always expected the worst to happen. But what those failures gave me was a sense of empathy. I was always in a position where I didn’t feel like I fit in. I was always getting fired from a job because I just couldn’t catch on, didn’t possess the secret that everybody seemed to know but me. It’s like the old adage of the guy walking around with his fly open; everybody knows it but him. Fast forward 30 or so years and I find myself confronting my fears in a warehouse. It was like being a prizefighter. I enter the warehouse; it’s large with fluorescent lights overhead. In the audience are all kinds of boxes with hardware and merchandise. And me being afraid of tools, I have to confront my fear of it and of working with others that I feel are more qualified, more able than I. But what I find is that I am actually thriving to a degree here. As the boxing trainer Teddy Atlas said of an up-and-coming fighter, “Let’s see what he has in the warehouse.” I have been able, through this job and in working with tools for the first time, to fix what was broken inside of me. So the idea of desire and resistance, which is an important element of my fiction, as I mentioned earlier, has come to fruition in my life in real time. Without my father I don’t believe I would have been a poet. My mother is important as well since we have so many similarities in our temperament.

I think the poetry in my book is good for men, young men in particular, to read. We are often told that as men, we are misogynists, no-good, etc. There are those who deserve those adjectives. But as men, we keep this world working. We are builders and as such, if we can build these incredible things, we can build each other. We need to hear this from men because we often hear those who are not men telling us what we are and what we should be. I think, as men, that if we can build complex and useful things, then we can build each other. If a father tells his son that he isn’t worth much in an attempt to have the son change his behavior, what often times happens is that the son believes what the father says. I think as men we need to take some of the narrative back and realize that what we feel, what we think, are important.

~~

Tony Asks Vince Gotera:

1.

Walter Mosley said that comic books profoundly influenced his writing and that he entered the world of fiction through comics at an early age. Your book, Dragons & Rayguns (Final Thursday Press, 2024), seems to pay a certain homage to the genre. Tell us how you entered the world of poetry.

Yes, Dragons & Rayguns is partially a tribute to the world of comics, and more widely pop culture in its many forms. As a young kid, I devoured Superman and Batman comic books, and then I discovered Marvel comics at about age 10 and that changed everything. I particularly remember appreciating Dr. Strange because he got to travel magically through so many strange dimensions and universes.

Before reading those earlier DC comics, I was very fond of the Classics Illustrated comic books. One of my favorites in that series was Time Machine. That H. G. Wells narrative really sparked my imagination. In Dragons and Rayguns, I have a poem called “All-Father,” which portrays Wells as his protagonist, The Time Traveler, going back to the primordial Earth and seeding life as we know it ... folks will have to read the poem to see how he does it. There are tributes like that in the book to other writers, such as sci-fi master Roger Zelazny and, more indirectly, Dickinson, Lovecraft, and Tolkien.

You can see the comics connection as well in the book cover, which was designed and created by my son, graphic designer Marty Gotera. I asked him for an image that incorporated a dragon and a raygun in comic book style. I think he really hit a home run, even using the title’s typography to symbolize Fantasy and Sci-Fi. The castle in the background may also allude to another genre in the book, Horror. Dragons & Rayguns is a collection of speculative poetry.

You also asked about my entrance into the world of poetry ... that’s a different story altogether. I was in first grade, I think, and on a ferry boat with my dad in the early morning, and I recall noticing the sun and musing about it. I already knew it was a burning ball of gas, probably from reading science-oriented comics (I remember I had a favorite one on nuclear physics!). When we got home, I wrote a short poem about the sun. I recall it was in quatrains, with alternating rhymes (I must have learned that from nursery rhymes). My mom sent the poem to my school and they put it in the school newsletter ... my first taste of publication!

2.

The poet/filmmaker Sam Tagatac likened the Filipino experience in America to a series of jump cuts in film. That is, our experiences are abruptly cut off from the past through our movements through time and space. Do you see your poetry as a way to bridge those "jump cuts" towards a deeper understanding of who we are?

The thing that’s fascinating about jump cuts in movies is that they present seeming disjunctions that then force us to envision parallels and correlations. The audience has to imagine and intuit the logical and causal connections that are the invisible glue of the narrative. I have tried to bridge those jump cuts in the Filipino diasporic experience with poems about Philippine history, culture, everyday life, and especially myth.

There are such poems on Philippine myth in Dragons & Rayguns, about aswang monsters and the Bakunawa sea dragon. The aswang are mythical creatures in the Philippines who are kind of all-purpose, like a Swiss knife or multi-tool ... aswang can be vampires, witches, shapeshifters, ghouls, and more, especially my particular favorite, the self-segmenting manananggal, a woman who can split at the waist, leaving her legs on the ground while her top half flies off to hunt in the night. In the book, I have a poem set in 1875, when the Philippines was a Spanish colony, which shows an aswang: “Her waist ripping, she lifts off, torn satin / shreds hanging, like bloody kite tails.” Another poem features a manananggal who has “slipped her tongue, / All ten feet of it,” into the open window of a sleeping pregnant woman; “She could almost taste the woman’s amniotic fluid, / Ever so sweet and pungent.” What I try to do is humanize these monsters by showing their essential humanity. I did something similar in two poems in the book about the Bakunawa dragon: why is he so enchanted with our world’s six moons he wants to eat them (we now have only one moon because the Bakunawa ate five before Filipinos figured out how to stop him). Incidentally, I have a book seeking publication now which is a novel-in-poems about two aswang lovers striving to survive as humans.

3.

I am envious of the fact that as well as being a poet, you are a musician. Has being a musician made you a better writer? What musicians, if any, have influenced your writing?

My immediate response would be that the two endeavors don’t overlap that much. I don’t think being a musician has helped me with writing as such. I do write about music, what it feels like to make music, and I write about musicians. I recently had a poem published in Rattle magazine that was a tribute to my old friend Bob Boynton, with whom I played in high school garage bands back in San Francisco. I write about famous musicians as well: in my first poetry collection, Dragonfly, I have poems about Carlos Santana, Elvis, Janis, Django, and Jimi Hendrix. In Dragons & Rayguns, Jimi also appears, along with Buddy Miles and Jack Bruce ... in heaven! The poem “Guitar Nebula,” about a cloud of star stuff in the sky, mentions “Jimi or Carlos or Eric or Eddie Van” (Clapton, that is). More recently, I wrote a poem about the band Fanny, which was founded by two Filipina sisters, June and Jean Millington. All these musicians have influenced my playing of music and, as subjects, my writing of poetry. I’ll probably compile a chapbook of music-related poems in the near future.

On further thought about the interconnections between music and poetry, I want to direct your question toward how word music—rhythm and rhyme, for example—is such a major part of my poetry writing. For example, in the book’s opening poem, “Time Lord Thief” (a poem set in the Doctor Who universe), I use slant rhyme, such as hooked / collect / intrigued; Chewbacca / Acme / Zarkov (those are more slant); won’t / purloined / siphoned /; and the full rhyme elegance / rayguns. I often apply consonance, like the play of m’s in the line “Hummingbirds, muskrats, mammoths, then Eve and Adam” from the poem “Creation, Discreation.” I frequently choose words more for their sound than their meaning. The animals in that line could have easily been eagles, earwigs, emu, if I had tried to work alliteration with the word Eve there (this alternate diction could also be assonance, the repetition of vowels, in this case the long ē).

4.

My uncle Al Robles had a term to describe Filipinos from San Francisco: Friscopino. You live and teach in Iowa. How has a sense of place impacted your work as a poet and/or educator?

I would like to think that I’m a “Friscopino” the way Al talked about it. Though I gotta tell ya, as a native San Franciscan, I bristle at the word “Frisco” ... that’s actually a city in Texas, you know. Ever since I can remember, from when I was a kid, I heard my fellow native San Franciscans say (and me too), “Don’t call it Frisco.” There was even a restaurant in the Western Addition maybe 50 years ago with that name! Often San Franciscans just say The City.

You mentioned that I “teach in Iowa”; I’m no longer a professor of English and Creative Writing, since I retired earlier this year. Coincident with that career change, though, is that just before that took place, I was appointed Poet Laureate of Iowa, so my teaching is now in workshops and readings and presentations at schools, libraries, colleges, churches, and public events. It’s all still poetry, though!

As far as how sense of place has impacted my work, in Dragons & Rayguns I have a poem addressing the mythical Jack Frost that arises from experiencing winter living in the Midwest, both Indiana and Iowa. San Francisco doesn’t have the same kind of winter, obviously, though I do remember a snowfall there in the ’70s, when snow stayed on the ground for a day or so ... hmm, there’s a poem there. I’ve written quite a bit about San Francisco, both about personal and historical topics, but none of those poems happen to be in this book because of its speculative bent. However, I did once write a speculative short fiction set in a futuristic sci-fi San Francisco, but that’s another literary genre! Or another story, if you will.

5.

In today's political climate of divisiveness, how do you see the role of poetry as a form of resistance?

During the early pandemic, in mid-2020, my poet friend Lee Harlin Bahan and I co-wrote a sonnet sequence, a chapbook called Corona: Virus, which is heavily critical of Trump’s handling of that national emergency ... that is poetry as a form of resistance. As Poet Laureate of Iowa, however, one of my messages is that poetry can be fun. It doesn’t have to be heavy all the time, though obviously that has its place, its own imperative. Light poetry is a kind of resistance to divisiveness because it can bring people together, through humor and laughter. However divided we are, our crucial humanity is kindred, especially with regard to rejoicing and happiness

In Dragons & Rayguns, for example, I have a series of haiku putting a light face on dark pop culture in Valentine season ... one goes “zombie scarfs candy / hearts that say XOXO / and taste like fresh brains.” The book has a Star Wars–themed poem that begins “Star Warsh is a laundromat” and features various characters like Luke and Leia washing their clothes (or should we say “warshing”?). The laundromat has a motto: “We keep you clean in Tatooine.” Dad jokes, I guess, but people have told me they appreciate this poem.

Of course, there are also serious poems in Dragons & Rayguns that take on weighty social subjects. The poem “Superhero” stars Tiger Woman, who undergoes sexist oppression and experiences feminist empowerment. “Old Soldier, New Love” takes on war and its aftermath, focusing on racism and one veteran’s salvation through a change of character. “Dragon-in-Training” dramatizes a teenager struggling with maturation and societal expectations; students in a class I recently visited told me they identified with this young dragon’s difficulties.

So yes, poetry can be resistance, but that is only one way to combat divisiveness. Poetry can also unite and bridge, connect adversaries through joy, and that’s what I hope I am doing with Dragons & Rayguns.

*****

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Tony Robles is the author of the poetry collections, Cool Don’t Live Here No More—A Letter to San Francisco; Fingerprints of a Hunger Strike, and Thrift Store Metamorphosis. He was named Carl Sandburg Writer in Residence by the Friends of Carl Sandburg in Flat Rock, NC in 2020. He was short list nominated for Poet Laureate of San Francisco in 2017. His poetry, short stories and essays have appeared in numerous publications. He earned his MFA in creative writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2023 and is currently a professor of creative writing in the MFA graduate program at Lenoir Rhyne University in North Carolina.

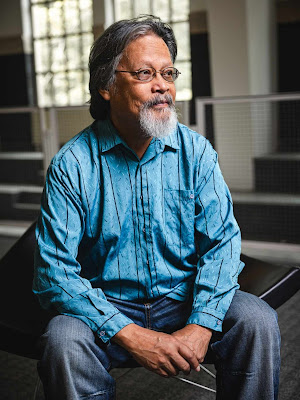

Vince Gotera is Poet Laureate of Iowa. He taught at the University of Northern Iowa for almost 30 years. Edited the North American Review (2000-2016) and Star*Line, the print journal of the international Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association (2017-2020). Poetry collections include Dragonfly, Ghost Wars, Fighting Kite, The Coolest Month, and Dragons & Rayguns. Recent poems in Dreams & Nightmares, The Ekphrastic Review, failed haiku, The MacGuffin, Philippines Graphic (Philippines), Rattle, Rosebud, The Wild Word (Germany), Yellow Medicine Review, and the anthologies Multiverse (UK), Dear America, and Hay(na)ku 15. He blogs at The Man with the Blue Guitar.

No comments:

Post a Comment